Early Learners Grow: Motivating and Supporting Teens

Many ABA providers today focus on early learners. There are several reasons, but one is the impact of early childhood learning on lifelong independence, social relationships, and ability to readily learn in adulthood, as supported by the CDC. But challenges don’t stop in those early years. Even for children who found success with early intervention, adolescence can bring its own unique obstacles and expectations that can be hard to adapt to, especially for learners on the autism spectrum who may already struggle to adapt to change.

There are many areas of adolescence that we’ll probably touch on over time in these blog posts–puberty, peers pressure and bullying, romantic and sexual relationships, school and career planning pressures–but a common concern I hear from parents is that it can be SO. HARD. to motivate teens.

The Why Behind Low Teen Motivation

If you’re a parent experiencing a dip in your teen’s motivation, or you are yourself a teen wondering why you can’t “get it together,” it’s important to recognize that this is such a common occurrence because of the significant changes going on in the brain in teenage years. As explained by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), the prefrontal cortex is slow to develop compared to other parts of the brain. This part is responsible for planning and good decision-making–including recognizing long-term consequences of seemingly small actions, or inactions, today.

Teens also are more predisposed than other age groups to stress, anxiety, and depression. This can be worsened by poor sleep patterns, which itself can be impacted by heavy electronic use characteristic of this group. These factors further reduce judgment and adaptability while increasing irritability, isolation, and inability to become adequately motivated by the things that once meant the most to them.

School Attendance & Academic Performance

Sometimes teens can lose motivation to do well in or to even attend school. We as parents know that this can impact the trajectory of your life, but to a teen who may be experiencing anxiety, learning differences, burnout, social stress, and just generally feeling different or less than than their peers, sometimes school and academic tasks feel hopeless, irrelevant, or like just another opportunity to feel badly.

First, avoid punishment. Instead, focus on the natural consequences of not attending school or not completing your schoolwork. Talk to your teen about what could happen and encourage them to come up with some natural consequences themselves. This offers an opportunity to make motivation relate to their personal goals and values. For example, for a teen who might want to go to college to play for their favorite team, a consequence of missing too much school could be not being accepted. For a teen who might struggle to identify any goals, especially if they are experiencing depression, identifying their values–the things that motivate them to get out of bed each day–might be your “in.” Even if they’re just motivated to play video games and hang out with friends, talking about how attending school gives more opportunities to see friends and gives natural breaks from games so they can perform even better when they log back on may help to make school attendance more meaningful.

Breaking big tasks into smaller, more achievable ones can help to make schoolwork more doable. Work with your teen to design an evening schedule where they can work on homework or study for smaller chunks alternated with quality breaks rather than allowing them to cram at the last moment before bed or pushing them to sit unproductively for hours when they’re already over it.

If your teen received early intervention, you might remember how giving a little bit of controlled choices can encourage collaboration and cooperation. For teens and school, allowing them to pick elective classes when possible or even, when possible, what education modality can have a huge impact on their willingness to lock in. I have seen some preteens and teens who were not successful in traditional public school thrive in online classes, even with little to no supervision. If this is a possible option for your family but you’re still unsure, you can make an agreement with your teen to trial online school for a determined period, with the condition that an inability to maintain attendance and passing grades will result in transitioning back to the previous school or to another option. Furthermore, work with your teen to identify if there are things that might help them to be more successful in getting up for school, getting homework done, or studying. Don’t allow them to manipulate you into big expensive purchases–in fact, that could reward the undesired behaviors instead!–but if noise-canceling headphones, a louder alarm clock, a laptop to type homework on instead of handwrite, or keeping their younger sibling out of the shared bedroom for an hour can change everything, they might be worth trying.

If schoolwork and attendance continue to be struggles, keep their teachers and principal in the loop. Collaboration and team problem-solving can be huge, as someone may catch a trigger, a possible accommodation, or other component that everyone else might miss.

“Adulting” Prep

Even at age 13 or 14, it’s practical to start thinking about what skills your teen will need as an adult and even starting to teach them this early. Learners who have higher support needs, like those who may need lifelong round-the-clock care, can still be taught independence that is compatible with their strengths to increase quality of life. Parents often think about household tasks, which are critical skills to teach, but should also consider conflict resolution, time management, creating and following checklists/schedules, accepting and responding to feedback and constructive criticism, setting goals and actionable steps to achieve them, managing money and budgeting, problem-solving, stress management, and making healthy choices in diet, exercise, and sleep are just as valuable–and are not automatic, but learned.

To start teaching, identify the smallest initial step or the step your teen is already likely to participate in and/or already independent in. When teaching how to create and follow schedules, for example, your teen may already be used to writing their football schedule on the family calendar; you can have them start plugging in football practices and games on their own calendar and tell them they can add to it whatever might be helpful to keep track of. From there, you can work on them designing a schedule for the week or each evening, allowing them autonomy while providing parental guidance. If teaching managing money and budgeting, you might recognize that your teen tends to spend allowance and holiday money as soon as they get it, only to ask for money just a few weeks later; you could have them open a bank account so they can view transactions and remaining balance in the bank’s app while still allowing to spend as normal. From there, you can work with them on placing themselves on a sort of weekly budget, where you encourage them to spend only a set amount each week and save multiple weeks for bigger purchases. For example, instead of spending all $300 at once, you can explain that he could spend $30 per week or could save across weeks when nothing is a strong “want” so that he could spend on bigger items later.

Something that I’ve seen with real families is parents being inconsistent in their expectations across family members. This can go both ways. Parents might expect little of their teen because of a diagnosis or the fights that could ensue while expecting more of their neurotypical child a couple years younger, which builds sibling conflicts and fails to transfer independence to the teen, even on responsibilities fully within their ability. Parents might instead expect their teen to stay on top of daily chores while letting siblings slide, or might expect grownup communication and problem-solving from their teen while themselves melting down when stressed, frustrated, or tired. Teens certainly take notice of situations that do not seem fair. Try to limit special treatment, but if there are circumstances that require different expectations or situations where you drop the ball in implementing consistency, be transparent. Teens who are only told “because I’m the parent, that’s why” don’t learn how to give others grace, how to respect others, or that the rules and expectations aren’t completely arbitrary.

All of this comes down to modeling. In teaching new skills, the best way to start teaching is to show the learner how it’s down and narrated steps and their rationale. From there, observe how the learner does the task themselves and provide feedback. Don’t just take over or decide to never let them do it again–we don’t need perfection, just collaboration, and feeling supported even through mistakes can make a big difference in a child or teen’s self-esteem. The next time(s), allow them to be independent under supervision again until you don’t need to intervene or correct anything. At this point, you can fade back to allow them independence, but check back in every so often to ask if they have any questions, ask if they need any help, and check their work. Checks can become less frequent over time as you find tasks to still be completed satisfactorily. If the teen seems to stop meeting expectations, return to a little bit of supervision and feedback until they are independent again, but do not jump in to do it for them.

Meaningful Independence

Earlier, we described how giving choices can still be effective for teens, as well as how making expectations relate to personal goals and values can make the expectations more meaningful and less detached. On a similar note, try linking new tasks and reinforcement to personal interests. Skill development is important, but so is enabling teens to be more in charge of their routines. Your teen might be resistant at first, but as they start to see that being given autonomy communicates respect for them as a nearly adult, many teens will rise to the challenge and look for ways to prove how grown they are.

For a preteen or young teen who loves animals, having the daily chores of walking the dog before dinner, filling the food and water bowls, and keeping track of how much food is left so more can be bought might be great first chores. For a learner who loves Legos, having them complete chores to earn an allowance toward a “Lego Fund,” where less interesting or longer chores earn more money and the learner can choose which they complete, might be motivating. For a teen who seems to just want left alone to listen to music and play video games in their bedroom, a good set of first skills might be how to respond in conflicts with other gamers online, researching the education and skills needed for careers of interest in music and gaming, handling frustration appropriately when siblings bother you, and starting to self-manage time on games to meet healthy guidelines.

Support for Parents

As with anything else with From the Nest, support comes “from the nest,” or from the home and parents. Even when you know that your teen is somewhat vulnerable to those brain changes, hormones, and poor sleep, and even when you’re trying to stay patient and compassionate, you might still feel overwhelmed, tired, disappointed, and frustrated.

One of the most important things you can do is to seek advice from other adults–other parents and professionals–whose opinions and knowledge in this area you trust. In fact, it may be appropriate in many cases to have a mental health provider evaluate your teen as a proactive measure to catch and treat deeper barriers like clinical depression, ADHD, anxiety, learning disorders, and more. Even if your teen is not found to have or be at risk for these diagnoses, the provider can provide guidance to promote healthy self-esteem and resources like local parenting and/or teen support groups and family wellness workshops.

Avoid power struggles. Instead, focus on collaboration instead of control. This will help to reduce rebellion from your teen–often behaviors that are maintained by negative attention and/or escape from things they don’t want to do–as well as prepare your teen for collaborative relationships and self-management as an adult in the near future.

Model the behaviors you want to see. Take your own baseline–notice how you currently respond to conflict with your teen. Do you yell? Do you berate or insult? Do you slam doors? Do you huff and growl and grumble? Then, next time, think about how you want them to respond in this situation, as well as any other conflict your teen has with authority figures or partners. Put those behaviors into practice yourself. Your teen may not immediately respond, but know that they are watching and learning from you how to love, respect, and support someone even when you disagree.

When they were a toddler, you quite literally celebrated the baby steps; similarly, celebrate the little wins and steps of progress now. Find opportunities to give specific praise to the positive behaviors you’ve seen recently, even if to you they might seem like things they “should” be doing and “shouldn’t” need attention for. Think about the last time a manager or one of your own parents complimented your work, your home, your parenting, or even your clothes or car. Most people enjoy having someone take notice of us, and calling out your teen’s good behavior will help to develop a trusting relationship that will further motivate behavior change.

Resources For This Week

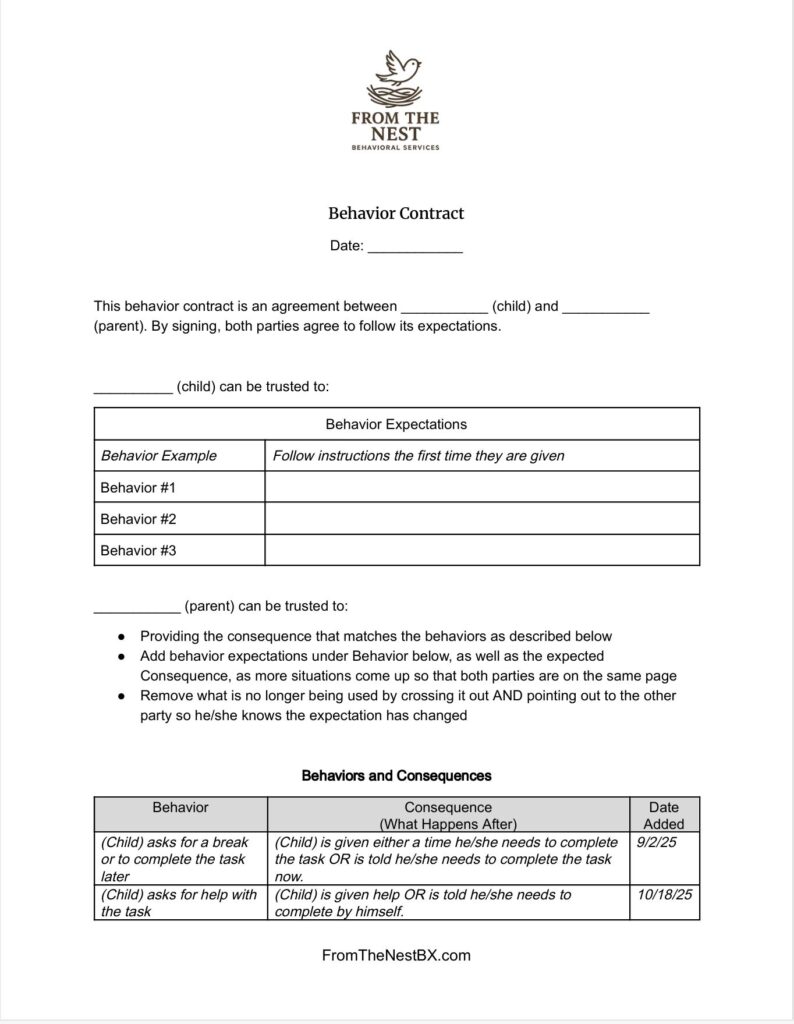

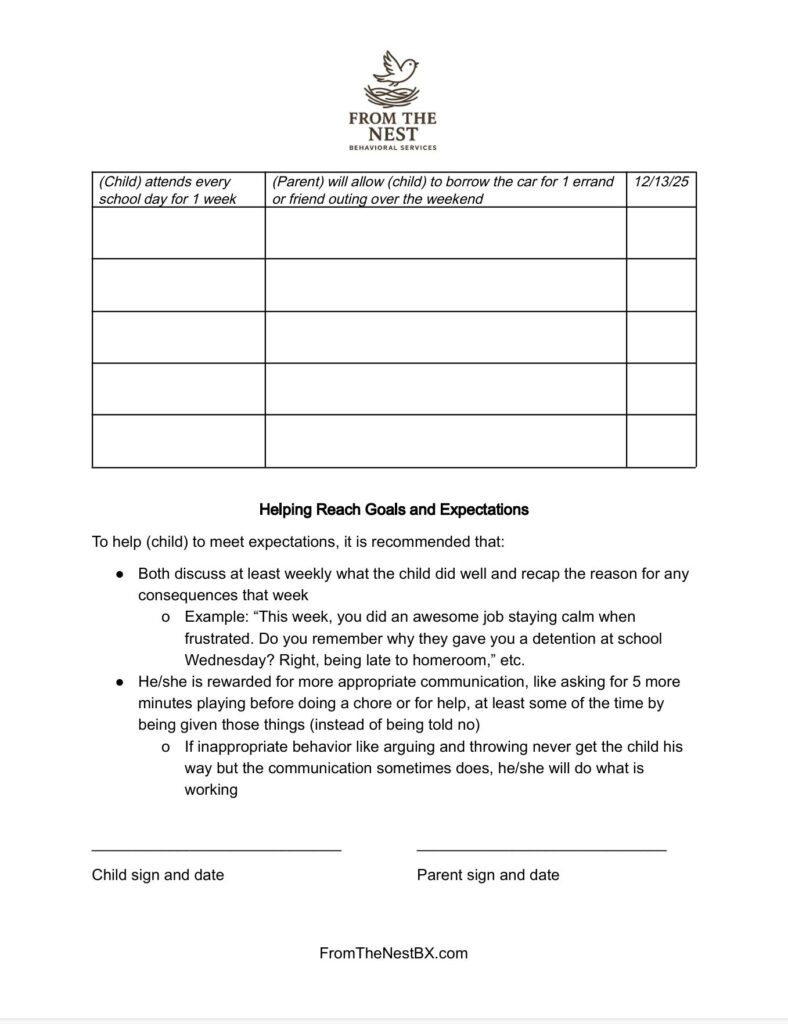

Sometimes talking and talking and talking about the same expectations or rules can get you nowhere. A behavior contract, on the other hand, can detail clear expectations of the child, as well as what the specific consequences will be. You can include both desired and undesired behaviors. While in ABA we prioritize reinforcement opportunities, as described above, there may be some natural punishers for undesired behaviors. Here are a few examples of what you might include in your teen’s contract:

- Attending school every day for a month will result in Sarah getting to choose her household chore assignment for the next month

- Missing school for a reason unapproved by Mom will result in Calvin studying on his weekend for 1 hour for every day missed to avoid falling behind on schoolwork

- Completing homework before bedtime, as checked and signed off by Dad each evening, will result in Raphael getting an hour of video game time before bed (Note: screen time before bed can impair sleep quality, but if this is a sufficient way to motivate and reinforce a behavior, sometimes you have to determine your priorities)

- Skipping class(es) will result in Dominic not qualifying to participate in basketball in the winter

Work with your teen to design rewards and to identify other consequences for behaviors, as well as to determine what criteria is achievable. Even if you expect your teen to want no part in the behavior change, you may be surprised to find that they just want to feel seen, heard, and supported. Both parent and teen should sign to the conditions of the contract and hold each other accountable. If one party isn’t fulfilling the terms they agreed to in writing, they shouldn’t be surprised if the other party falls off as well. Then, if any modifications are needed, these can be agreed to and added to the contract so they can be referenced later. Keep the contract in an easy-to-see location, like the refrigerator. Try this for at least 6 weeks to see if you can work as a team to find conditions that get both parent’s and teen’s wants and needs met, even if some compromises on the little details might need to be made.

Access an easy-to-use template HERE to try a behavior contract with your child.

by Britt Bolton, owner/lead BCBA

Look at our FREE Printable Resources page for routine visual supports, checklists, goal-setting worksheets, teen and young adult guides to jobs and self-advocacy, and more!