10 Skills Found in Jenga (and Other Things)

“I want to make one thing clear,” a parent told me in an initial assessment. “I don’t need someone coming in here to play games and mess around doing the fun stuff all session. It needs to be work.”

I knew immediately where she was coming from.

I’ve met a lot of parents, grandparents, aunts, older siblings, family friends, teachers, principals, speech and physical therapists, and even other ABA professionals who have said basically the same. We need to go go go. We need to chip away at the “problems”–from the genuine safety concerns to the inconveniences–by grinding away at the same triggering stimuli until the child complies. We need to be firm and to discipline anything less than acceptable behavior and to have real treatment going on. They’re not going to learn if you’re just goofing off the whole time. No games. Limited breaks. Progress doesn’t take giggles, tickles, or high-5s, it takes of blood, sweat, and tears–sometimes literally.

So there’s no blame for the individual parent. But, one time, I asked a caregiver–

“Do you know how many skills can be found in Jenga?”

Games: Jenga, Guess Who, and I Spy

1.) Recognizing the other person’s turn: The learner has to be able to follow the rules of gameplay, as well as visual clues in the game and sequences, in order to know it is their opponent’s turn

2.) Waiting for the other person’s turn: This isn’t a repeat. Not only does the learner have to recognize that it’s the other person’s turn, they have to have the impulse control to actually wait, even if the opponent takes longer than the learner would like or the learner already knows the perfect next move

3.) Behavioral inhibition/delayed gratification: Along the same lines as general waiting, the learner has to resist the urge to blurt out an answer before the other person has finished their question or to take the block that’s sticking out of place, as any of these moves can feel good to act on in the moment but lead to undesired natural consequences

4.) Sustained attention: By using a fun, fast-paced activity, we can build a learner’s ability to stay plugged into an activity for longer durations, which can then be generalized to other tasks or less exciting activities by gradually introducing them

5.) Responding to another’s request: Being able to appropriately to someone’s question or hints, like in Guess Who or I Spy, or cueing, “Your turn” builds reciprocal, or back-and-forth. communication

6.) Sportsmanship: As another way to build social reciprocity, the learner learns how to encourage others, make kind and supportive comments, share in another’s excitement, and respond appropriately to another’s disappointment or frustration

7.) Rule following and following instructions: The learner may need to follow both written and verbal expectations or instructions in order to be successful in the game

8.) Information recall: The learner may have to remember later what the instructions said at the beginning of the game. This skill is needed in day-to-day life, like remembering how many pages the teacher said to write or what Mom asked you to do before you can go to your friend’s house

9.) Listener responding by function, feature, and class: This typically comes up as LRFFC in ABA terminology but simply means recognizing items when given their descriptive properties, as seen in Guess Who and I Spy

10.) Adjusting behavior based on feedback or previous outcome: Once previous games have been played, the learner is able to develop the ability to recognize ways to adapt based upon the needs of the game in order to be more successful in the next round. This isn’t a valuable skill because of an ableist view that the autistic child should adapt to everyone else–this is a valuable skill because everyone finds opportunities where adjusting how they respond, what face they make, what time they leave the house, what tools they take with them, and other behaviors differently impact success.

Hidden (or Less Recognized) Skills in Other Activities

Here are some skills you may not have thought much about in other play or routine activities:

Playing at the playground

1.) Spatial awareness: judging how close you are to the swing hurtling toward you or how far you are from the adult responsible for you

2.) Scanning and processing complex visual information, or a scene: seeing what is available to play on, who you can play with, and if danger is present

3.) Cause-and-effect, or consequences: noticing if the broken ladder could be dangerous or what happens if you let go of the monkey bars

4.) Self-advocacy: standing up for oneself if the swing is pushed too high, another child mistreats you, or you would like your turn on the slide

5.) Knowledge of personally identifying/safety information: If separated from your adult, being able to communicate your name, who you were with, a phone number, or other details

Build with blocks, a marble track, or similar toy sets

1.) Joint attention: Sometimes this can include being able to follow a gesture or point. The learner and their playmate share focus on the same things while building together as a means of building social interactions and relationships

2.) Perspective taking: Both builders may have a unique plan in mind, which also requires–

3.) Flexibility and conflict resolution: Sometimes both builders can have a turn doing things their way, or a compromise can be found.

4.) Coping or calming strategies: When pieces won’t fit together right or the structure you’ve worked hard on crumbles, you may need to use methods like taking deep breaths, leaving the activity for a break and returning later, or other strategies to avoid yelling, throwing items, or hurting yourself or others

5) Descriptive, phrased requests and labels: “I need the long yellow piece,” “No, the blue one,” “That’s the biggest marble!”

Going to the doctor

1.) Body part identification: If you don’t know where your mouth is, it can be hard to know what is expected when asked to open it, even with gestures.

2.) Asking for a break: When overwhelmed or nervous, especially if the alternative might be a meltdown, it is perfectly reasonable to ask for someone to hold on, and doctors and nurses can better respond to this than less clear visual signs of distress.

3.) Tolerance for unpredictability: While the same elements can happen across routine wellness checks, they may not happen in the same order, the same exam room, with the same nurse, or with the same materials. Additionally, a less typical appointment, like an emergency visit, can come with its own uncertainty, which can be triggering.

4.) Desensitization: This can be a harsh or apathetic-sounding word, but gradually–at the learner’s pace–building tolerance for uncomfortable, scary, or generally disliked by necessary parts of an exam can help them feel more secure and more heard, while helping professionals to get the most accurate information in safe conditions

5.) Tolerance for low- and high-sensory environments: A doctor’s visit, including the exam itself and the wait beforehand, can either be super overstimulating or very quiet, long, and boring

This is just an incredibly small look at not only the skills that help learners to be independent, safe, and able to access maximum reinforcement, but also can answer why a learner may seem to struggle in a particular area. By pulling skill-building into fun and routine activities, we can provide teaching under relaxed conditions that actually better promote the learning process than drilling, diving headfirst into the most intense and exactly triggering events, and rushing the process.

As mentioned in a previous post, ABA is a marathon–and that is okay! As long as safety remains the most immediate priority, it is okay to take the tiniest of baby steps of progress in gaining skills because that is still progress. At From the Nest, we know that your child’s wellbeing rests heavily in our hands, and we respect that trust. Therapy doesn’t have to be work and, in fact, it shouldn’t be.

by Britt Bolton, owner/lead BCBA

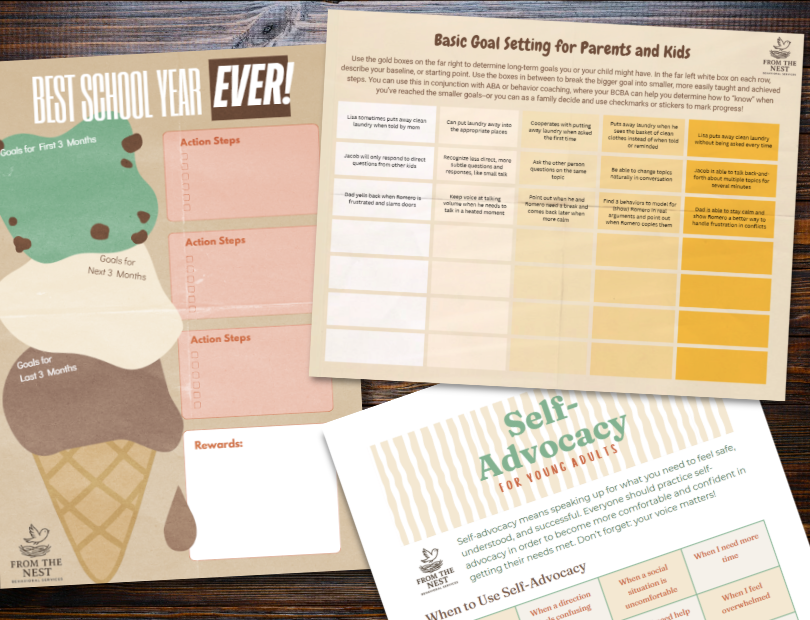

Look at our FREE Printable Resources page for routine visual supports, checklists, goal-setting worksheets, teen and young adult guides to jobs and self-advocacy, and more!