Medical Rule-Outs

I had a learner once who fell asleep literally on his feet. He would be walking down the hallway or playing with his RBT in the center, then, seemingly out of nowhere, be in a deep, snoring slumber. In those moments, he was near impossible to wake up and even when we were successful, he’d be back asleep in minutes. We often had to call his mom to come pick him up, most of the time still in the first half of the day, and if we didn’t and took data on his sleep, he would remain asleep until time to be picked up!

Now, I’ve seen some pretend sleeping from kids, but this was 100% authentic deep sleep, and I was growing concerned. Mom insisted he slept about 12 hours every night without issue, showed as much on the sleep logs we gave her to complete, and felt we needed to just continuously wake him up and keep him awake to get through the day. She said it was definitely him avoiding things he didn’t want to do. But on my end as the BCBA, we were looking at a medical rule-out before we could go any further.

The Ethics

It’s not that I didn’t want to “deal with” the inconvenience of waking and keeping up a child who just wanted to sleep. What parents often don’t know (but we try to explain in these cases) is that our ethics code as BCBAs puts us in a spot where we have to rule out medical concerns before we attempt to tackle something we’ll call “medically uncertain” (my phrase, not the BACB’s):

Code 1.05 Practicing Within Scope of Competence: Behavior analysts practice only within their identified scope of competence. They engage in professional activities in new areas (e.g., populations, procedures) only after accessing and documenting appropriate study, training, supervised experience, consultation, and/or co-treatment from professionals competent in the new area. Otherwise, they refer or transition services to an appropriate professional.

Code 2.01 Providing Effective Treatment: Behavior analysts prioritize clients’ rights and needs in service delivery. They provide services that are conceptually consistent with behavioral principles, based on scientific evidence, and designed to maximize desired outcomes for and protect all clients, stakeholders, supervisees, trainees, and research participants from harm. Behavior analysts implement nonbehavioral services with clients only if they have the required education, formal training, and professional credentials to deliver such services.

Code 2.12 Considering Medical Needs: Behavior analysts ensure, to the best of their ability, that medical needs are assessed and addressed if there is any reasonable likelihood that a referred behavior is influenced by medical or biological variables. They document referrals made to a medical professional and follow up with the client after making the referral.

Code 3.01 Responsibility to Clients: Behavior analysts act in the best interest of clients, taking appropriate steps to support clients’ rights, maximize benefits, and do no harm. They are also knowledgeable about and comply with applicable laws and regulations related to mandated reporting requirements.

TL;DR: As much as mom’s insights into and experience of the daytime sleeping was valued, we were ethically bound to make sure we were acting in the learner’s best interest and our own scope of practice before approaching it simply as a behavior of concern.

When Behavior Isn’t the Whole Story

As a parent, it’s natural to look at a child’s behaviors and assume they’re “just being a kid” or “acting out.” But sometimes, behaviors that seem purely emotional or behavioral can actually have a medical explanation. That’s where a medical rule-out comes in. A medical rule-out is essentially a process of checking whether underlying health conditions could be contributing to a child’s behaviors. It doesn’t mean your child’s behavior isn’t real or valid—it just ensures nothing physiological is being overlooked.

Imagine a child who suddenly becomes irritable, struggles with sleep, or has unexpected outbursts. The first instinct might be to try more behavioral strategies. But if the root cause is something like thyroid imbalance, chronic pain, or even gut issues, behavioral strategies alone might not help—and could even be frustrating for both child and parent.

Common Concerns

Some conditions (but not all) that are often explored in rule-outs include:

- Sleep disorders – Even mild sleep disruptions can look like hyperactivity or emotional dysregulation.

- Allergies or gut sensitivities – Digestive discomfort often shows up as mood or behavioral changes.

- Neurological conditions – Seizures or migraines sometimes present primarily with behavioral changes in children.

- Endocrine or metabolic issues – Hormonal imbalances, thyroid issues, or blood sugar fluctuations can affect mood and attention.

- Vision or hearing problems – Struggling to see or hear clearly can create frustration, avoidance, or withdrawal.

- Ear or tooth infections or irritations – Pain can lead to head-directed self-injurious behaviors, like banging one’s head on hard surfaces or hitting oneself in the face.

- Medication sensitivities, including adjusting to new medications/dosages – Adjusting to medications, even ones a learner has been on for awhile, can lead to any number of behavioral side effects, like aggression or restlessness, or physical side effects, including impacted sleep, reduced or increased appetite, which may impact motivation and more

- Constipation – The discomfort of constipation can lead to increased irritability and rectal digging

The Process

A medical rule-out usually starts with a conversation with your child’s pediatrician or specialist. They may ask detailed questions about behavior patterns, sleep, diet, and growth. The doctor may then order lab work or screenings, as well as refer to another specialist if needed.

It’s often a collaborative process. Parents, doctors, and sometimes behavioral professionals work together to ensure the whole picture is considered. Your doctor may even ask your child’s teacher to complete questionnaire-type screenings or answer questions on their observations of your child in the classroom.

If any medical concerns come up during this process—such as new or adjusted medications, referrals for additional therapies, surgeries (like ear tube placement), or the use of over-the-counter aids like laxatives or melatonin—please keep your child’s BCBA informed. Sharing these updates helps the BCBA monitor how medical changes may affect your child’s ABA treatment.

When you provide this information, the BCBA will mark the change on your child’s behavior and skill graphs. This makes it easy to see whether the medical update is followed by progress, new challenges, or no significant change. With this data, you and your ABA team can better understand what is effective and make informed adjustments to support your child’s progress.

More Informed Care

Medical rule-outs aren’t about labeling your child or second-guessing parenting—they’re about making sure the whole team has the full story. When we rule out medical causes, we can feel more confident that the interventions we try—whether behavioral, therapeutic, or environmental—are hitting the right target, and this helps us to be more ethical and mindful in the care we provide for your child.

If your child’s behaviors are new, intense, or unexpected, it’s worth having a conversation with their healthcare provider. Even small adjustments in health or routine can make a world of difference.

by Britt Bolton, owner/lead BCBA

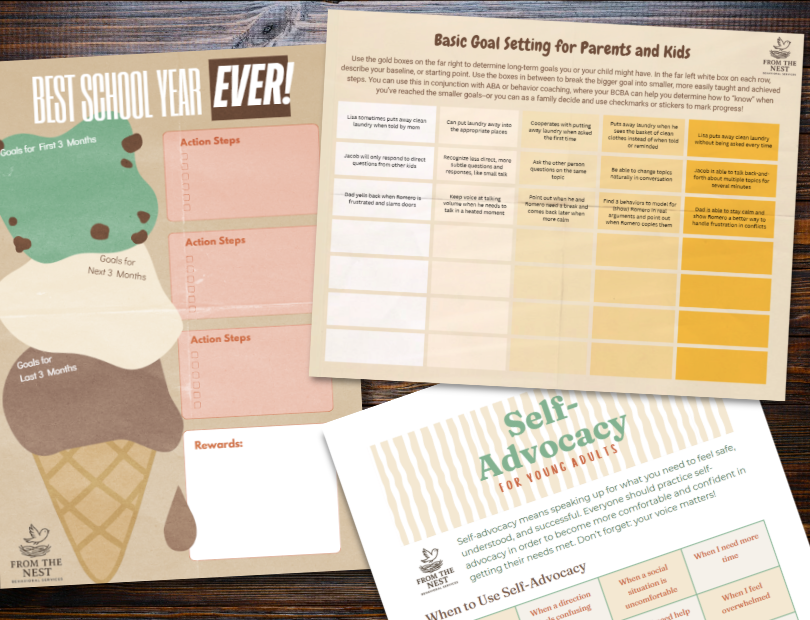

Look at our FREE Printable Resources page for routine visual supports, checklists, goal-setting worksheets, teen and young adult guides to jobs and self-advocacy, and more!