December 2025 Vocab of the Month: Reinforcement

Picture a young person working her first job in a clothing store in the mall (yes, a real, brick-and-mortar mall; pretend it’s the 90s if that helps). She clocks in on time and alternates between stocking shelves and helping customers until her first break at 10:27. She stops by a vending machine a short walk from her store and buys a soda. That caffeine helps her power through until her lunch at 1:34, when she decides to swing by the food court to get some pizza from a cute guy working the cash register. They laugh and chat the full 20 minutes, then it’s time for her to hustle back down to the store to clock back in before she’s late and risks missing out on the perfect attendance bonus this month.

Now why are we talking about some hypothetical (90s) retail worker? Because she helps to represent our vocab of the month and the ways we access it in typical day-to-day–even as adults.

Reinforcement is any consequence that increases the future likelihood of a behavior. If a behavior happens more often because of what followed it, reinforcement occurred. When our retail worker clocks in on time, she earns a paycheck and is meeting criteria to earn a bonus. She will be more likely to continue to clock in on time and to continue working this job than if she were to receive a neutral consequence, like no paycheck or bonus, or a punishment, like a reprimand or being fired. The paycheck and bonus are both forms of delayed reinforcement. At the vending machine, the worker’s behaviors are putting in money and pushing a button, with the reinforcement being receiving the soda she chose. This is a more immediate reinforcement, where the reward occurs right after the behavior. She will be more likely to continue to use this vending machine if she keeps reliably receiving these sodas than if she received nothing, the wrong item, or sometimes nothing (inconsistent reinforcement). The ongoing social response from the cute pizza guy increases the likelihood of the retail worker continuing to laugh and chat. In fact, the retail worker hustling away doesn’t mean it stopped being reinforcing–it means keeping her job and earning the attendance bonus were more motivating!

Here’s a more visual breakdown:

| Behavior(s) | Reinforcement | What’s More Likely to Occur Next Time |

| Clock into work on time | Earn paycheck and bonus | Continuing to come to work on time |

| Putting money into the vending machine and pressing the button | Receives desired soda | Continuing to use that soda by putting in money and pressing that button |

| Laughs and chats with pizza guy | Pizza guy provides attention by laughing and chatting back | Continuing to come flirt with the pizza guy |

As you can see, reinforcement can take many forms and can happen constantly throughout a person’s day. The good things we receive (positive reinforcement) and the “less good” or even bad things that go away (negative reinforcement) shape our behaviors for the next days, weeks, months, and years as we recognize the pattern, or the contingency.

And importantly, none of this requires us to consciously label what’s happening. Our retail worker doesn’t need to think, Ah yes, I am contacting delayed positive reinforcement in the form of a paycheck. Her behavior still changes. Reinforcement works whether or not we are aware of it, which is just as true for adults as it is for children.

In ABA, we use this same process but we do so with intention. Rather than waiting for life to randomly shape behavior, we identify skills that will meaningfully improve a person’s independence, communication, safety, or quality of life. Then we arrange the environment so reinforcement reliably follows those skills.

This might look like:

- A child gaining access to a preferred toy after appropriately requesting it

- A learner receiving attention and praise for attempting a new or difficult task

- A teen earning increased independence as they demonstrate responsibility

- An adult putting chores on pause for the evening as a self-reward for a productive day

- Moving bedtime back an hour moving forward for a preteen who shows he can manage to still get up and ready for school on time in the mornings

Just like with our retail worker, reinforcement only “counts” if it actually increases the behavior. If it doesn’t, we adjust. Reinforcement is empirical, not theoretical.

In ethical ABA practice, we are thoughtful about how reinforcement is arranged. While negative reinforcement is unavoidable in real life (finishing work so you can stop working, for example), programs generally prioritize positive reinforcement—especially for learners who have historically experienced high demands with little payoff. This is often the moment where discomfort shows up: “But aren’t we just rewarding people for things they should already be doing?” The answer (ignoring the loaded “should” in there) is often yes! If we encourage continuing a desired behavior by making it more worth the learner’s while, everyone wins.

Some parents understandably conflate this with bribery. The key distinction is that reinforcement is planned and predictable. Bribery is reactive and typically occurs during problem behavior (“If you stop screaming, I’ll give you…”). Reinforcement happens after a desired behavior and is clearly tied to it (“When you do X, Y happens”). Our retail worker isn’t being bribed to show up to work on time. Expectations are clear, consequences are consistent, and she chooses to keep engaging in the behavior because the outcome matters to her. ABA works the same way. Early skill acquisition often requires contrived or synthetic reinforcement: things like tokens, edibles, or extra screen time that don’t naturally follow the behavior outside of teaching situations. These are tools, not endpoints. As skills strengthen, ABA programs intentionally fade:

- How often reinforcement is delivered

- How immediately it’s delivered

- How artificial it is

And shift toward natural reinforcement, or outcomes that occur in everyday life.

Eventually, the reinforcement for communicating isn’t a sticker; it’s being understood. The reinforcement for completing work isn’t candy; it’s finishing more efficiently, earning independence, or accessing preferred activities, much like our retail worker earning breaks, paychecks, and social connection. Reinforcement isn’t something ABA invented. It’s the system all of us are already operating within. ABA simply makes it visible.

When we understand reinforcement, we stop seeing it as manipulation and start seeing it as what it truly is: information about what matters to someone, what motivates them, and how learning actually happens. Used ethically and intentionally, reinforcement doesn’t create dependence. It creates opportunity.

by Britt Bolton, owner/lead BCBA

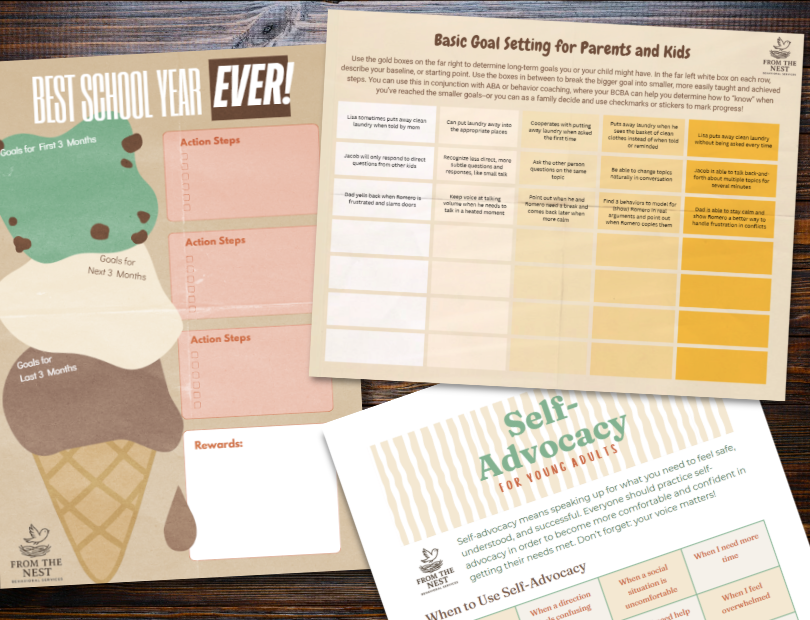

Look at our FREE Printable Resources page for routine visual supports, checklists, goal-setting worksheets, teen and young adult guides to jobs and self-advocacy, and more!