Function Junction, What’s Your…Function?

Everything in the house is calm. Okay, stick with me here–really, everything in the house is calm. Your partner is in the living room watching some TV. The kids are putting together a puzzle in the dining room. You’re in the kitchen popping some popcorn for movie night. It’s still early in the evening, everyone enjoyed dinner, the kids never play this well together. Bliss!

The microwave whirrs and the kernels pop loudly until the beeping that alerts you it’s ready to be poured into your bowl. You click its door shut and exit the kitchen.

“Kids! The popcorn’s–“

There in the dining room, your daughter is frozen, looking between you and your son, who is covering his ears and bumping his head against the wall. The puzzle pieces are strewn everywhere. “Dad, he just–“

“What happened?” you ask as you rush over to protect his head. He knocks your hand away.

“I don’t know!” your daughter says. “We were just sorting out the pieces with similar colors. It came out of nowhere!”

Out of Nowhere

You might already be trying to figure out what’s going on here. Maybe you can think of things that have similarly triggered your own child–the beeping of the microwave, the sound competing with the TV in the next room, sister not playing fairly, a missing piece. But you might also be thinking, sometimes it really does just seem to come “out of nowhere.”

Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) works in large part by identifying the function of a behavior. We recognize four functions: attention, access to tangibles (though this can be a little misleading–I’ll get to that in a minute), escape or avoidance, and automatic. It isn’t abnormal for a behavior, or something someone does, to serve more than one function. For example, a child screaming, crying, and throwing themselves to the ground when told it’s time to clean up is likely to be engaging in these behaviors to both escape (or temporarily avoid) the task of cleaning up while also trying to access the tangible toys they have been playing with. A teen who starts banging on the bathroom door demanding their shower time as soon as anyone else tries to get ready is likely to be trying to access the shower, trying to access someone’s attention, and maybe even automatically reinforced by the behavior itself (loudly banging around is fun).

Attention: As many point out, a better way to conceptualize this is sometimes “connection-seeking,” in particular a behavior where the individual is trying to gain social attention for the sake of social attention. Examples include a student speaking out in class, a toddler hitting your arm when you’re on the phone, or a child saying, “Look at me!” so you watch their cartwheel. In some situations, the attention function corresponds to escape or access as a way of gaining socially-mediated escape/access, which means another person providing that access (like having you hand them their toy that’s out of reach) or escape (like cuing you to offer a break).

Escape: This can include both completely “getting out of” something and merely putting it off for as long as possible. As noted to the left, escape might be socially-mediated or automatic, where the behavior itself serves to get the learner out of whatever the “thing” is. An example of automatic escape is a driver locking their car doors after they get out–they escape (or in some cases temporarily avoid) the consequence of having their car broken into or stolen. Escape can also go hand-in-hand with access to tangibles, described below.

Access to Tangibles: Like I said, this can be a bit misleading. We say, “tangibles,” but we don’t always mean a specific item you can touch or hold. Yes, it often does include items or objects, but can also include places, activities, and actions. Sally asks you to push her higher in order to swing higher. Enrico runs from the classroom and outside to get back to the playground. Priya screams when you take her tablet away because she wants the video to keep playing. In many situations, a behavior may be to escape something non-preferred in order to access something preferred; some people shut off their alarms to escape the annoying sound and get back to sleeping!

Automatic: “Automatic” encompasses behaviors where the behavior itself is its own reinforcement. Sometimes these behaviors relieve boredom and/or provide sensory regulation, like tapping a pencil on the desk top, bouncing your leg, or humming in class. Sometimes these behaviors provide temporary relief or a competing sensation with pain or discomfort. For example, a child might seem happy, relaxed, and engaged, only to begin hitting themselves in the jaw region. After a trip to the doctor, he’s found to have an inner ear infection.

But How Do You Know?

BCBAs use multiple methods to hypothesize the function(s) of a behavior:

- Observing what happens before, during, and after the behavior, if safe to do so

- Interviewing parents, teachers, and sometimes other relevant parties on what the have seen happen, what seems to work best, and what they hypothesize the functions(s) to be

- Testing different antecedent (before the behavior) and consequent (after the behavior) strategies to determine what works

- Completing something like the Questions About Behavioral Function (QABF) and/or Functional Assessment Screening Tool (FAST), which ask somewhat repetitive but nuanced questions to determine in what conditions the behavior is most and least likely to occur

By using some of even all of these elements together, a BCBA can determine what the most likely functions are. From there, we can determine the best possible interventions. A strong treatment plan focuses not only only how to respond to the behavior, but also–even more importantly–how to modify the environment or instructions to prevent the behavior and functionally-equivalent replacement behaviors, or skills that can be taught to help the learner still get their needs met in safer, more appropriate, more reliable ways.

Here’s an example of why this is important: both Megan and Kaleb hit their classmates during peer play time. Through observation and teacher report, it is determined that Megan hits when another student takes her toy or the equipment she was about to use, while Kaleb hits other students when the teacher is playing with another child. Even though the behavior, environment, and activity are the same, the same interventions will not inherently help Megan to advocate for herself (escape/access) and help Kaleb gain the teacher’s attention. Without the skills to more effectively get what they want, Megan and Kaleb are likely to continue hitting classmates.

You Can’t Always Get What You Want

The most common resistance BCBAs receive to this is, “Well kids can’t get their way all the time.” Absolutely they can’t–no one can! But making modification to help prevent the behavior and teaching functionally-equivalent replacements are not about helping the learner to endlessly get whatever they want, when they want it, all the time.

In the beginning of ABA, it is important to consistently and frequently reinforce the new skills. So, yes, there will be a lot of blowing the bubbles if Emily asks, “Bubbles,” or giving Michael breaks from schoolwork if he gives the hand signal, or giving India a Skittle for going in the potty. But once the learner shows consistency, skills like tolerating being told no, tolerating waiting, choosing between 2 alternative options, and maintaining the skill for less frequent rewards or praise can be developed. I often call this Phase 1. As a parent myself, subject to the same judgment from others and internal guilt as many other parents, I recognize it can feel really uncomfortable to feel like you’re rewarding behaviors a child “should” be doing anyway or to be giving in every time they ask. In fact, it can often seem to totally go against our own experiences in childhood or what society has deemed to be the “gold standard” of parenting! But we have to first teach that this new skill is worth the child engaging in, especially if the unsafe/disruptive behavior has become easier or their go-to.

ABA is a marathon, not a sprint. By establishing the functions, we can help to get there quicker, safer, calmer, and kinder.

by Britt Bolton, owner/lead BCBA

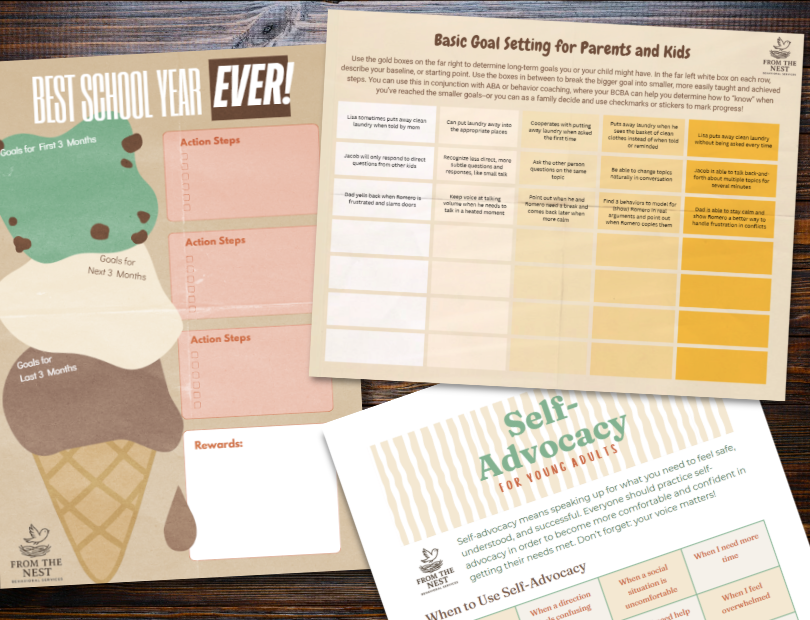

Look at our FREE Printable Resources page for routine visual supports, checklists, goal-setting worksheets, teen and young adult guides to jobs and self-advocacy, and more!