Intro to Autism Spectrum Disorder

There are tons of resources online about Autism Spectrum Disorder, but not all of them are accurate or helpful to parents who might be trying to decide if ABA therapy, behavioral consultation, or other resources might be right for their child.

In fact, there are a lot of things that could be said about autism in this “intro” post alone, but maybe breaking autism down into its DSM-5 diagnostic criteria, what those items mean, and how we tend to approach them in ABA will help to shed some light on what to expect throughout your child’s life and what to expect from intervention.

A. Persistent deficits in social communication and social interaction across multiple contexts, as manifested by the following, currently or by history (examples are illustrative, not exhaustive, see text):

1. Deficits in social-emotional reciprocity, ranging, for example, from abnormal social approach and failure of normal back-and-forth conversation; to reduced sharing of interests, emotions, or affect; to failure to initiate or respond to social interactions.

Learners who meet A1 criteria may struggle to engage in conversation, which often looks like not responding to others’ questions, not asking questions of their own, straying off topic, and ending conversations abruptly, like by walking away. As part of not staying on topic, they might find it difficult to interact with another person in activities or on subjects they themselves do not find especially interesting, whereas many neurotypical individuals recognize that developing and maintaining friendships, romantic relationships, healthy interactions with coworkers, and parent-child bonds often requires compromising in the sense that you won’t always be able to focus only on what you want to–there is a natural give-and-take.

In ABA therapy, we can use strong personal interests as our “in” to develop conversational skills before transitioning toward less interesting topics. For example, for a teen boy with expansive knowledge on baseball, conversations can be based around how to play, a recently televised baseball game, an experience attending a game, the history of a specific team, and other subcategories of baseball, and staff or even peers can follow these interests to teach the learner how to generate his own questions and more. Once the learner self-assesses their own conversational skills strongly, including feeling calm and comfortable initiating and joining conversations with less predictability, we can start to introduce other topics by slowly expanding from baseball (“Oh, that game you said you went to last summer sounds like a lot of fun! I didn’t go to a baseball game, but I went camping. Have you ever gone camping?”). As the learner again feels calm and comfortable, we can expand further still by teaching how to follow what someone else may want to talk about, which may have nothing to do with baseball.

What’s important is prioritizing that give-and-take; if the learner should be able to “give” by allowing others to choose topics, others should be expected to do the same!

2. Deficits in nonverbal communicative behaviors used for social interaction, ranging, for example, from poorly integrated verbal and nonverbal communication; to abnormalities in eye contact and body language or deficits in understanding and use of gestures; to a total lack of facial expressions and nonverbal communication.

The theme of A2 is “nonverbal communication”–anything that isn’t said but still communicates meaning. Part of the challenge for some neurodivergent individuals to process facial expressions and body language–as well as integrate both spoken (vocalized, signs, device, pictures, etc.) and non-spoken communicative elements into their own communication–is limited or lack of eye contact.

“Today’s ABA” is overwhelmingly moving away from targeting eye contact due to feedback from autistic persons that eye contact can be uncomfortable, anxiety-inducing, and even painful. Instead, it is completely appropriate for the learner to orient toward the speaker in any way that promotes noticing these little details, whether that’s looking generally at the speaker’s face or simply facing somewhat in the direction of the speaker. Once this skill is developed, we can use roleplay, more synthesized question-and-answer (traditional DTT), feedback, and self-assessment to teach the meanings behind common forms of unspoken communication.

Picking up on more subtle, indirect communication is not only a social skill, but a safety one. For example, ideally, a person will see smoke, smell something burning, and recognize they need to leave the building and call 9-1-1. But for some people, environmental cues are not direct enough communication on what response is needed, and smaller details can be missed. It’s invaluable to teach learners how to interpret cues in a safe, supportive learning environment so that they can form a foundation of basics and generalize to novel (new) experiences.

3. Deficits in developing, maintaining, and understanding relationships, ranging, for example, from difficulties adjusting behavior to suit various social contexts; to difficulties in sharing imaginative play or in making friends; to absence of interest in peers.

It’s common, sadly, to hear from parents who are concerned that their autistic child is not able to make friends or participate in birthday parties, sports, school clubs, and other social childhood activities with the ease of their other children, their friends’ children, or their child’s classmates. That can be heartbreaking for parents who may themselves be more social and see the value in forming these relationships early.

Learners who struggle with A3 criteria fall into this category. They may as young child have a hard time playing at recess and playdates because they don’t understand the “rules” or expectations of pretend play. They might seem to prefer self-stimulatory behaviors, like pacing, spinning, hanging from playground equipment, repetitively moving or manipulating an item or set of items, or swinging alone for long durations. They don’t seem to understand how to join the group even when they do seem interested in participating.

Ethical professionals recognize a key thing here: it is perfectly fine to not be a social butterfly. If a learner appears to prefer playing alone, having their personal space, and playing the same way or with the same things over and over, whether or not it’s “functional,” that is not detrimental. Where this becomes something that is medically necessary to intervene on is if rigidity in play means that leaving that activity or those items being unavailable results in unsafe behaviors; if a lack of apparent interest in peers is again more of an issue of limited attention to the environment as described above and may contribute to impaired safety; if the learner cannot self-advocate in situations where others may bully, mistreat, or manipulate them; and if any of the above limits the learner’s access to environments and opportunities, which can impact their quality of life.

ABA therapy can target all of these skill areas, as well as, again, use learner interests to fade in opportunities they may not otherwise seek out. While working on these skills, we want to honor learner assent, or willingness to develop these skills, and if the learner expresses distress, it is time to hold off, modify the approach to be more supportive and preferred, built in emotional regulation and coping strategies, and possibly recommend integrating (or moving completely toward) mental health supports to better treat the emotional symptoms of social development.

B. Restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities, as manifested by at least two of the following, currently or by history (examples are illustrative, not exhaustive; see text):

1. Stereotyped or repetitive motor movements, use of objects, or speech (e.g., simple motor stereotypies, lining up toys or flipping objects, echolalia, idiosyncratic phrases).

B1 does a great job giving examples of what stereotyped or stereotypic behaviors include. In addition to lining up or flipping objects repetitively, autistic individuals may engage in echolalia, or repeating words, sounds, or phrases, often from others in the environment or media (scripting). I knew of one learner who loved to repeat all the current and past Geico commercials, and I’ve had several kids repeat the reprimands they had heard from parents or teachers whenever they’ve break a classroom or home rule! Idiosyncratic phrases are phrases borrowed from other sources, like videos, to which the individual has assigned unique meaning, often correlated with its original meaning in the source material. For example, if in a video a character cried, “Help! I’m lost!” when separated from their parent in a new and busy place like an amusement park, the child might cry out, “Help! I’m lost!” when overwhelmed and scared in a new, busy place, even if still with their parent and not truly lost.

As explained above, unique ways of playing with toys and other items is not inherently “bad.” I would never intervene on or stop a learner from lining up their toy cars during play just a parent, teacher, or someone else thought it weird, inconvenient, or otherwise a problem. The main situation where we would intervene is if the repetitive behaviors are potentially harmful, like throwing a chair to watch how it lands or hitting oneself in the face with a clothing hanger, both of which I have seen in real life. Another situation where we would intervene is if the behaviors in some way infringed upon someone else’s safety or autonomy, which I explain more below in B2.

I might additionally model for a learner additional, not alternative, ways to engage with items. In the example with the learner lining up toy cars, I might show how to drive them on the floor and table, crash them into each other and furniture, and act as rides for other small figurines. Not to show that their way is wrong or “not functional,” but as more options for keeping themselves entertained, engaged, and regulated, as well as ways to play with others if opportunities arise and they want to. And if the learner rejects these ways, no problem! At least this adds to their play skill “toolbox” if they choose to try it in the future.

2. Insistence on sameness, inflexible adherence to routines, or ritualized patterns or verbal nonverbal behavior (e.g., extreme distress at small changes, difficulties with transitions, rigid thinking patterns, greeting rituals, need to take same route or eat food every day).

If you’re a parent reading this blog post, there’s a good chance you’ve experienced this with your child. Kids in general can excel with and prefer routines. But, with some neurodivergent children, routines, which promote predictability, reduce uncertainty, and reduce negative emotions like fear and anxiety, can become absolute and necessary. In these cases, the smallest change can lead to intense behavioral episodes, and parents may find themselves walking on eggshells to avoid setting off the child, which only further ingrains the inflexibility.

As touched on above, neurodivergent children may even become rigid about things that infringe on someone else’s safety or autonomy. For example, I assessed a learner whose mother couldn’t wear ever wear any type of jewelry because the learner would scream, cry, hit her mother, and try to rip the jewelry off of her–including nearly tearing earrings through her lobes. Some would say that’s simple, just don’t wear jewelry–but, as they were starting to see similar behaviors when other girls and women in the family wore jewelry, they were concerned how the learner might respond to a teacher, nurse, babysitter, or others, especially those who might not be aware ahead of time, and they recognized that it was not a fair imposition for anyone.

How do we work on this in ABA? We could–theoretically–push the learner “cold turkey” into triggering events like transitions, different foods, non-preferred clothing textures, and more. Some BCBAs will say that this is good for the learner, that they will have to do these things eventually anyway and can’t get their way all the time, and teach staff and parents how to desensitize themselves to learner distress.

We could do that–and some in ABA have and still do–but this is not in line with our ethics. Even in exposure therapy within mental health services, exposure is gradual and the individual assents to each step of the process. This is the way From the Nest tackles increasing flexibility. While it is absolutely imperative to differentiate that we do not provide a mental health services, ABA targets skill building, including in routines and thinking patterns. We should still work gradually, meeting the learner where they are (baseline) and building tolerance skills slowly from there. We should also respect the learner’s general wellbeing (do no harm) and autonomy, which we target by teaching self-advocacy (no, I don’t want to, can we do it later, I need a break, etc.) and putting teaching on hold and analyzing for needed modifications to teaching protocols at the first sign of distress.

3. Highly restricted, fixated interests that are abnormal in intensity or focus (e.g, strong attachment to or preoccupation with unusual objects, excessively circumscribed or perseverative interest).

Some autistic people may become “obsessed,” to use common terminology, with not only topics but items or even people. The latter is often the more concerning and potentially dangerous situation (though preoccupation with dangerous items, like weapons, can also be unsafe). I have known several adolescent male learners who, upon entering puberty, became fixated on specific female staff in and unwanted way to where even seeing them elsewhere in the ABA center or out in the community could lead to running to them, trying to touch their breasts, hugging on or rubbing against them, and other similar behaviors. Sometimes this is less extreme and physical, where an individual might talk at length about a particular person. Another learner comes to mind, who was facing potential consequences in school because his preoccupation with a female classmate was making her uncomfortable and her parents were beginning to voice that they felt the preoccupation was harassment. All of these examples are with male learners only because of personal experiences, but this can easily occur with female learners as well.

One way we approach B3 “deficits” or challenges is through work on perspective-taking. If the learner better understands how unwanted touching of and talking about someone can make that other person and third parties feel–scared, uncomfortable, self-conscious, embarrassed, angry–they can start to learn how to adjust their behaviors. Another way we can approach perseveration, or fixation on items, people, or other stimuli, is by setting specific parameters for acceptable, safe interest and when that is appropriate. For a few examples, we can talk more about your special interest after homework is done. We can talk about things we appreciate about our friend but not about their body and not in a way they have already told us they don’t like. You can talk to Sarah in private one time about your feelings for her, but you cannot talk to her about this around other people because she might be embarrassed, and you cannot keep talking about it if she asks you to stop or turns you down. You can sit by Darius in every class and lunch if he is okay with it, but if he moves somewhere else, is sitting at a full table, or chooses other friends for a project, it is not okay to keep following him or asking him to move–you can ask tomorrow if you can sit by him and accept his response.

4. Hyper- or hyporeactivity to sensory input or unusual interests in sensory aspects of the environment (e.g., apparent indifference to pain/temperature, adverse response to specific sounds or textures, excessive smelling or touching of objects, visual fascination with lights or movement).

B4 is similar to B2 for many individuals on the autism spectrum. While B2 focuses on rigid routines and thought patterns, B4 focuses on rigidity with sensory elements, and sensitivity to one is often correlated with sensitivity to the other. Additionally, B4 covers the complete opposite–a lack of sensitivity–which can similarly cause distress in kids and parents if the child cannot recognize injuries or potential for injuries because of a lowered pain response.

The ABA teaching techniques will be much the same as what I describe above for B2, but additionally, teaching learners how to recognize physical signs of injury, like bruising, blood, burns, or rashes; how to recognize potential consequences or safety risks of common stimuli like hot stoves and ovens, scissors and knives, and moving vehicles; and the need to report injuries to a responsible adult and how can help them to stay safe.

C. Symptoms must be present in the early developmental period (but may not become fully manifest until social demands exceed limited capacities or may be masked by learned strategies in later life).

A common criticism of ABA therapy is that it teaches learners to mask, or cover signs and symptoms of their diagnosis. It is true that some providers in the past and present have prioritized masking-type skills like eye contact, reducing any stimming (self-stimulatory behavior, like flapping or repeating words), playing only how others label “functionally,” and following rigid conversational scripts. This criticism is founded for as long as bad practitioners are practicing badly.

But, by teaching valuable safety, social, communication, self-care, and other skills, we again add to that “toolbox” I mentioned earlier, or set of skills that the learner has the ability to access when they want or need. I never want to pressure a learner to believe they have to have conversations all the time on things they don’t care about or have to play with their cars only by driving them on a track or have to change themselves to make others more comfortable or happy. But I absolutely will teach skills that will keep them and others safe and will be optional things they can access if in a situation where not having those skills would impact their quality of life.

D. Symptoms cause clinically significant impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of current functioning.

The above criteria describe the social, communication, and daily functioning areas impacted by autism. D summarizes these challenges in way. If an individual was unable to maintain conversations, did not engage in play with other children of the same age, and was fixated on insects, these qualities in themselves would not be problems but more of personality traits. But when they impair the individual’s ability to form social relationships when wanted or needed, to care for themselves, to keep themselves safe, and/or to access learning, play, and other opportunities, they become areas that BCBAs and other professionals must analyze for possible growth opportunities.

E. These disturbances are not better explained by intellectual disability (intellectual developmental disorder) or global developmental delay. Intellectual disability and autism spectrum disorder frequently co-occur; to make comorbid diagnoses of autism spectrum disorder and intellectual disability, social communication should be below that expected for general developmental level.

In other words, autism is only diagnosed if intellectual disability or global developmental delay don’t better explain the challenges, although learners sometimes have any combination of these diagnoses. For autism and intellectual disability to be diagnosed, social communication, or communication used in social interactions, has to be less developed than expected in other learners of the same age.

I don’t have an ABA-ism to add specific to this, but it does raise the point that some skill strengths and areas of development can be related to diagnoses other than autism. For some insurance payers, ABA therapy can only treat autism symptoms, or teach skills specific to autism needs. There are also some medical and mental/emotional needs that ABA or From the Nest may not be the right fit for. In these situations, referral to more appropriate resources helps families to access what may provide more help and support.

Information Applied

Not every ABA provider will approach the above criteria in the same way, and not every approach will be used in every case. In some ways, this is great! We want treatment plans, or the goals and interventions for a learner, to be individualized so that the unique learner accesses unique care that is actually relevant to their day-to-day life (what’s called social significance in our sphere). But take some time to get to know how a provider approaches medical necessity before committing to treatment from them. There are still plenty of bad actors in this field, unfortunately, but the more we can help parents to learn what to look for and what to look out for, the more we can propel ABA toward the changes that need to take place systemwide.

by Britt Bolton, owner/lead BCBA

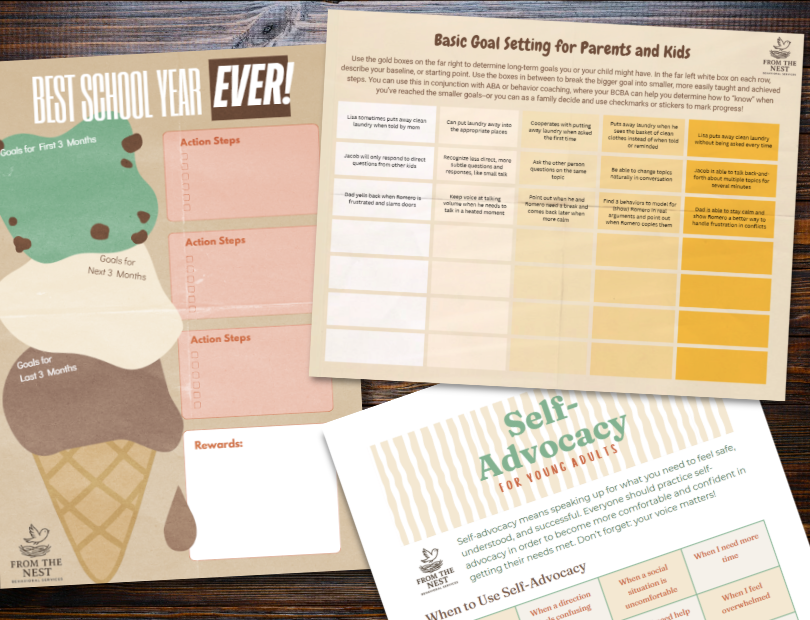

Look at our FREE Printable Resources page for routine visual supports, checklists, goal-setting worksheets, teen and young adult guides to jobs and self-advocacy, and more!