Replacement Behaviors

“So how do we make them stop?”

Some variation on that question comes up pretty frequently across a BCBA’s caseload. It’s behavior therapy. Many families who seek out ABA or are referral have things their child engages in that are unsafe, inappropriate, disruptive, rude, loud, embarrassing, annoying, exhausting, or bad. Those are the words we hear sometimes, anyway. And parents, educators, other therapists–they’re just ready for those things to STOP.

When we ask how we “make” them stop, we’re really asking a different question entirely. And the answer to that question is our jumping off point for treatment.

Function Junction Flashback

In November 2025, we looked at the four functions of behavior that build the foundation (or a foundation) of ABA. These are the drivers behind the behavior wheel, so to speak: Attention, Access (to items, places, people, etc.), Escape or avoidance, and Automatic (or sensory).

Sometimes, a behavior has two or more functions. In the case of an infant, they will scream and cry (two behaviors) to get the attention of someone nearby, to get their bottle or pacifier, to try to get mom to stop cleaning them with that cold wet wipe, and because it feels good or makes other sensations (hunger, earache, etc.) feel less bad.

Same Destination, Different Car

Mom and dad know Timmy’s hitting other people is not it. Mom is tired of bruises on her arms. Dad is embarrassed when his brother-in-law makes jokes about it at family get-togethers. Both are worried about Timmy’s baby sister’s safety as she grows…and now while she’s still so small and fragile. School is over calling about it and would rather have mom pick him up than keep trying–and sometimes failing–to keep other students and staff safe. For the past few months, mom parks her car in the school lot after she’s sent him inside, knowing that, more likely than not, the call will come before she’s even made it home. He’s getting older and bigger. How are they supposed to keep him safe from security guards, well-meaning strangers, and police if he starts hitting in public? How is he supposed to be able to access the same things other young adults do: football games, dates, part-time jobs?

These aren’t bad parents. These are parents who love their child deeply and know that aggression isn’t going to be tolerated and might put Timmy and others at significant risk of danger. They’re afraid of not being able to stop it.

So let’s say the BCBA determines the functions of Timmy’s hitting others to be escape from “demands” (instructions or less-preferred activities) and access to desired items and activities. In other words, when Timmy hits, he’s consciously or subconsciously anticipating the hit being effective in avoiding what he doesn’t want in order to get (or get back, if it’s been removed) what he does want.

From here, the BCBA determines how Timmy can safely get those wants and needs met. If the BCBA were to just put the behavior on extinction–or somehow cut off all sources of reinforcement to the hitting–Timmy no longer has a reliable means of getting needs met. Not only is it dangerous to just cut off reinforcement to something like hitting, but the alternative may not come naturally or easily to Timmy, meaning he may find a more appropriate way, may find a less appropriate way, or may be extremely dysregulated while he can’t communicate.

“No,” “stop,” “don’t do that,” and other reprimands are not replacing anything. So what would replacement behaviors, or replacement skills, ideally look like for gaining access or avoiding something?

- Timmy asks for a break

- Timmy asks for a different activity

- Timmy asks to modify the activity, like where it is completed or with what materials

- Timmy points to what he wants

- Timmy uses sign language to ask to do the activity “later”

- Timmy chooses between two alternative, similar options if the one he wants isn’t available

The list goes on. And here we’re able to see therapy goals emerge.

From Knowing to Doing

Understanding replacement behaviors is one thing. Figuring them out in the middle of real life—when everyone is tired, overstimulated, and already dysregulated—is another.

The parents I talk to don’t struggle with caring or trying. They struggle with having a simple way to slow down and think through:

- What’s actually happening?

- What need is my child trying to meet?

- What could I teach instead?

That’s exactly why I put together a free, informal guide you can print or keep on your phone. It walks through those questions step by step, without clinical language, charts, or perfection required. While I will always recommend working with a BCBA to make sure the real functions of the behavior are found–because not having it exactly right can have real consequences, including the behavior continuing or increasing instead of getting worse–in some cases, particularly where your child has told you what they want or you have seen the pattern consistently, this tool can help break down problem-solving from conceptual level to actually doable. You might not need a BCBA to break down that the tantrum in the checkout is to get access to the candy.

When to Tag us in

If the behavior is dangerous, escalating, or interfering with your child’s ability to learn or connect, it’s time to tag in a BCBA. Needing support isn’t failure—it’s responsible care. You don’t have to figure this out alone.

by Britt Bolton, owner/lead BCBA

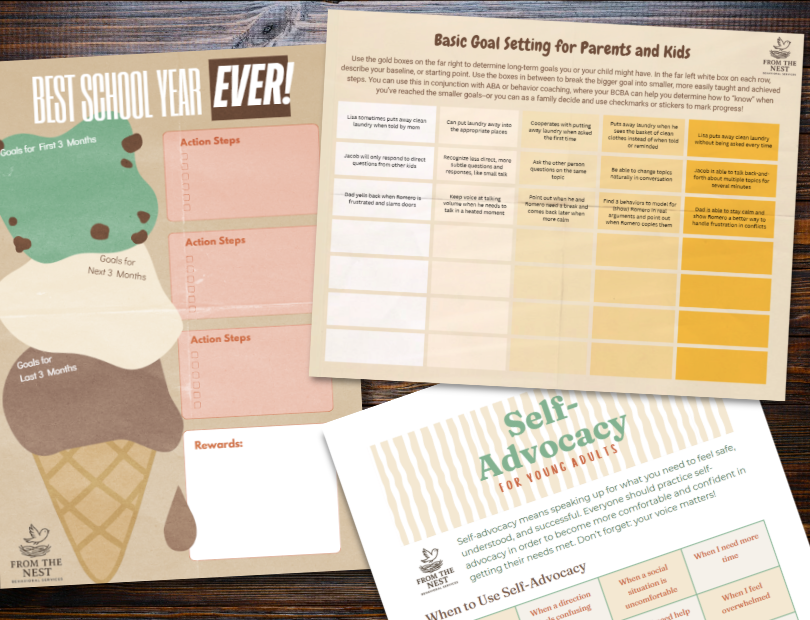

Look at our FREE Printable Resources page for routine visual supports, checklists, goal-setting worksheets, teen and young adult guides to jobs and self-advocacy, and more!